Looking back at what we thought in 2012 about 2021

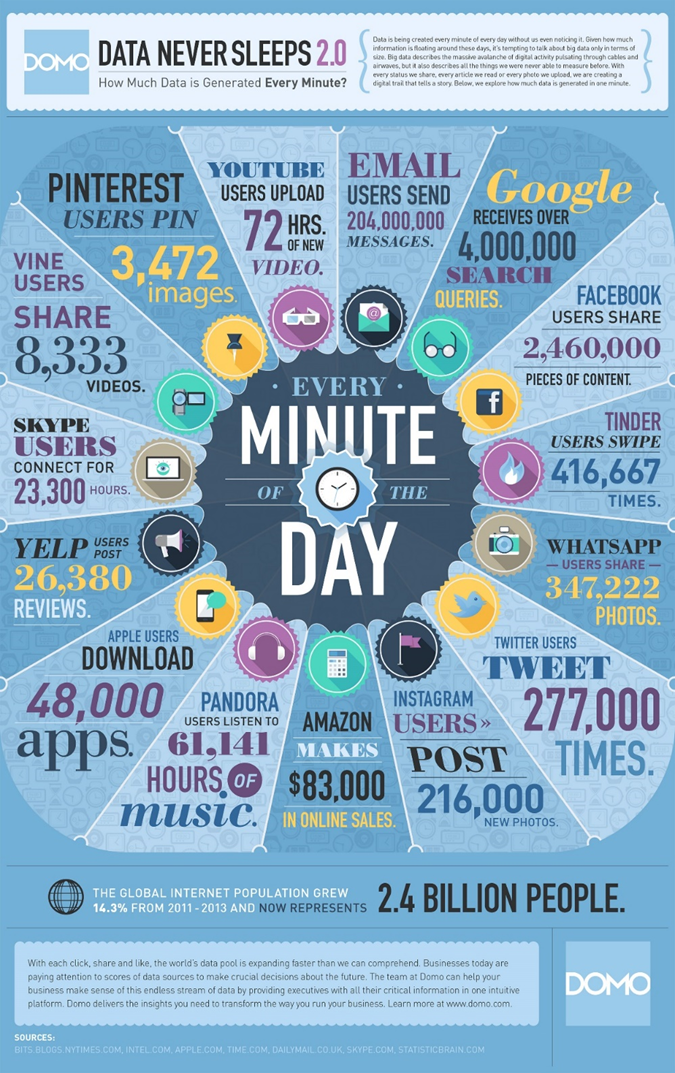

In 2012, according to Domo, YouTube users uploaded 72 hours of video content per minute. In that same minute, 23,300 hours of Skype conversations were occurring, Vine users shared 8,333 videos, and 62,242 hours of music streamed via Pandora.

In desktop virtualization and VDI solutions world, the message was:

"Work is no longer a place. Meetings and workspaces are mobile. Desktops, once considered devices, are increasingly delivered as services from the cloud – giving employees easy access to their apps and data from any laptop, smartphone, or tablet. Simplicity is disrupting complexity. The long-held focus on "building and operating" computing systems are rapidly moving to ‘aggregating and delivering’ services from a wide range of sources… IT is no longer exclusively in the decider's seat.” - 2012 Citrix Annual Report

Virtual Desktops were in their infancy, with limited practical use cases and no ability to incorporate a graphics card to mimic the feel of a desktop/laptop computer or give end-users at the time the ability to consume and interact with all the rich media content around them. The technology was not there yet. It would be the very next year, March 18, 2013, to be exact, when the technology pioneered initially by NVIDIA and Citrix for Boeing seven years earlier would be released to the general public as the NVIDIA GRID K1 card. The NVIDIA GRID K2 card, for more intensive vGPU workloads, would be released May 11, 2013, even though Chrome, Internet Explorer, and the Firefox browsers had been able to take advantage of a GPU to improve performance around 2009.

NVIDIA K1 and K2 vGPU cards enabled VDI customers (initially only working with the XenServer hypervisor) to consume and create graphics-rich content similar to their PC and Mac friends.

Immediately, every company using desktop virtualization acquired and deployed this technology to improve the desktop and application virtualization end-user experience, enabling end-users to create or take advantage of the volumes of new content created every minute, use webcams, watch training videos. Right? That is how it went, right? Not so much.

End-users don't need GPU. The CPU can handle the graphics content that virtual application and desktop users need to do their jobs. That was the consensus in 2013, even though every major browser could take advantage of GPU to improve content delivery, and January 29, 2013, saw Microsoft roll out Microsoft Office 2013, the first version of the ubiquitous business productivity suite incorporating GPU acceleration.

Flash forward to 2021 as we approach the 10th anniversary of the release of the first NVIDIA K1 card, bringing GPU to VDI environments. How has the world changed?

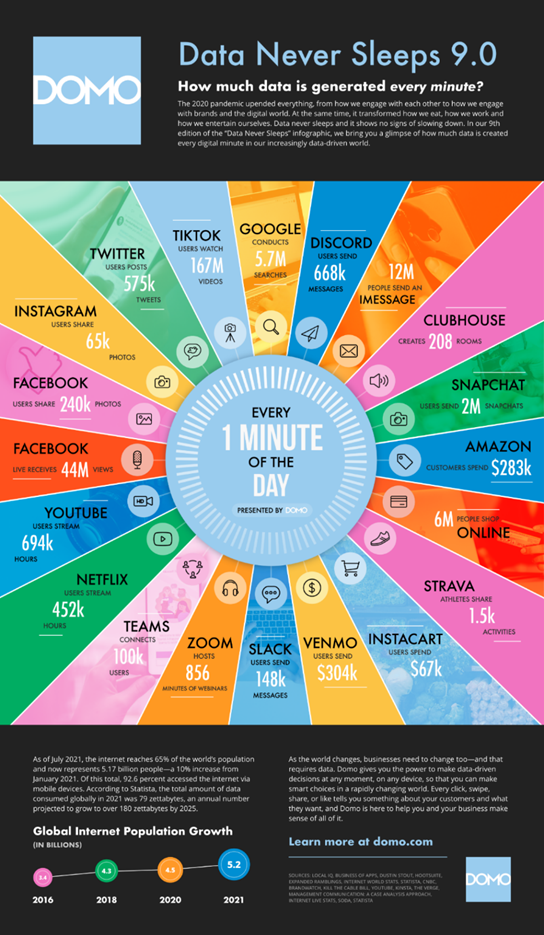

In 2021, YouTube streams 694,000 hours of video content, Netflix streams 452,000 hours of content (hopefully not at work), there are 100,000 end-users connecting with Microsoft Teams, TikTok users watch 167,000,000 videos, and this little company called Google executes 5.7 million searches. Every minute!

Thanks to advances in technologies, like VDI and global disruption caused by the pandemic, Global Workplace Analytics believes that 25-30% of the U.S. workforce has been working from home in 2021. Setting that in context, 16% of global companies have a fully remote workforce. Owl Labs reports that 62% work remotely occasionally and that 44% of companies do not allow any remote work.

While the sentiment around VDI solutions has evolved, and virtual desktops can support most use cases, there is still a significant portion that believes end-users do not need a graphics card or vGPU to do their jobs effectively. Even though the content end-users are interacting with are increasingly more visually oriented than ever before including browser, webcam, streaming training content, webinars, online meetings, and Microsoft Office to name a few.

Adding graphics cards is not a requirement for all VDI use cases and will not always provide a benefit. Warehouse workers scanning barcodes, for example, or core banking applications doing nothing more graphically intensive than pulling up an image of a signature card or archived PDFs are potential examples.

Beyond the historic desktop virtualization strongholds of the financial services, healthcare, government, education, energy, and manufacturing, in 2020+, industries like architecture, engineering, construction, media, and entertainment are testing and delivering some of the most graphically intensive applications and use cases the world has to offer and finding success with VDI.

When a prospective employee with the right skillset can be anywhere in the world with a good internet connection, able to connect and collaborate just like they are in the next office, the talent pool gets bigger, staffing becomes a bit easier, retention options expand, and things like COVID are not as scary or potentially as debilitating.

During the pandemic, banks leveraging VDI were able to send half of their employees home to work as soon as the original shutdown occurred, and branch lobbies were closed. Departments split with half going home so that no one employee could infect and take out an entire team.

These banks maintained operations, taking care of their customers, albeit through new and creative means like opening new accounts in the drive-through. For those with vGPU, team meetings with webcams via Zoom, WebEx, GoToMeeting, or the like with chat/collaboration tools to help the culture and connectedness bridge the gaps in physical space, work got done, and new customers were acquired because customers could get their needs addressed in a challenging time.

Today, for $4-6 per end-user per month for the average employee, end-users with virtual desktops that can leverage graphic-intensive applications, graphics enriched content that can come through browsers, like Chrome, webcams, streaming media, or even that Excel spreadsheet with a crazy number of macros, working from almost anywhere. There is no need to take my word for it; we are proving this out daily with strings of ongoing proof-of-concept engagements and sizing assessments for each customer's application set, sample data, and use cases.

One drawback to VDI has historically been the knowledge required to make it work well. That problem is no more with firms, like Whitehat, specializing in managing VDI for small and large companies alike, introducing appliance-based VDI solutions, like Titanium HCI for Citrix or VMware Horizon, or any number of cloud or as-a-Service desktop offerings.

Suppose you have not experienced what VDI is capable of in 2021 or have Citrix, VMware Horizon, or even Teradici and cannot do anything previously mentioned. In that case, it might be worth taking another look at what superpowers VDI solutions can enable when employees have the full capabilities of virtual PCs to do their jobs, support the company mission, and be able to see, interact, learn, and consume content in an increasingly visually rich world.

.png?width=799&quality=low)

Leave Comment